What to expect from the terrain to the weather

Over Mountains and deserts, through ghost towns during rain, hail, and possibly landslides. Just a quick bike ride through the diversity of our great nation.

Have I mentioned how intimidating this half of Route 66 is? Between the mountains, the desert, the ghost towns, not to mention the weather variability, and all while having to cycle everywhere, it keeps me up at night! Usually, I try not to think about all these obstacles because they would scare me out of wanting to do the ride. Today, I’m going to tackle my fears straight on, so let’s do what Mark Watney would do and break it all down. As an aside, the fictional character is from my actual alma mater, so I feel a kinship to his nerdiness.

Elevation

First, let’s talk elevation. The route starts in Amarillo at 3,645ft, which is more than the 18ft above the sea level of Oakland, where I live. The route peaks near the volcano of Cerro Bandero, New Mexico, where it also crosses the Continental Divide at 7,900ft before going down and back up to 7,335ft at the Arizona Divide, and then gradually seesawing its way through Cajon Pass, 4,290ft, and back to sea level at the Santa Monica pier.

Why does this matter? The higher the elevation, the more the body’s ability to deliver oxygen to working muscles is reduced, which lowers VO₂ max and endurance performance. VO₂ max decreases by about 6–7% per 1,000 meters (3,280 ft) above sea level. So when I land in Amarillo, I’ll already have a 6-7% decrease in ability, and when I reach the peak a week later, I’ll be down an additional 6-7%. Climbers in the Tour de France, for example, slow noticeably above 7,000ft. Over time, my body will adapt, but this process takes weeks to months, which is not going to help since this ride “should” only take about three weeks.

Mountains

The southernmost point of the Rocky Mountains runs near Santa Fe, which is along Route 66. However, I have opted for a more direct route skirting the Rockies, which are the largest mountain system in North America. However, I will still be cycling across the Sandia Marzano Mountains just east of Albuquerque.

The Continental Divide will be in the Zuni Mountains just south of Gallup. That day, I’ll have to bike 100 miles from Grants to Gallup since there are no hotels along the bike route, while attaining the highest elevation, 7,900ft, and the second most feet of elevation gained in a day, 3,996ft. Eastern AZ will present a nice descent until just outside of Flagstaff, where we’ll climb 1,500ft in 34miles.

Once we leave Flagstaff, we’ll be climbing out of the basin and over the volcanic San Francisco peaks until more ascending near Oatman and the border with California. Finally, we’ll cross another high point at the Cajon Pass as we traverse the San Gabriel and San Bernardino mountains, where we finally roll into Los Angeles.

Desert

Lots of people like deserts, think of Sedona, Joshua Tree, Las Vegas, Santa Fe, etc. I’ve decided that I dislike the desert. I prefer lakes, rivers, lush green valleys, places where there is an obvious fresh water Garden of Eden-like vibe. Unfortunately, for the most part, the landscape of this ride is going to be pretty arid, dry, and hot except for a few select places.

Although Amarillo seems like it would be in a desert, it’s actually in the High Plains of the Texas Panhandle. In New Mexico, we move into the largest desert in North America, the Chihuahuan, near Albuquerque, and it’s known for having the most cactus species of any other desert in the world. Ow!

Through Arizona, we’ll encounter the Painted Desert, where there is a meteor crater and the Petrified National Forest Park. Finally, the Mojave Desert, home to Death Valley, the lowest, hottest, and driest point in North America. Temperatures regularly exceed 100°F even in October. There aren’t a lot of services, there is intense UV radiation, and flash floods occur. It can be surprisingly cold at night and sweltering during the day.

The heat will be a significant issue to overcome as it causes thermic stress. This refers to the physiological strain placed on the body when it struggles to maintain optimal core temperature, especially in hot or humid conditions. Essentially, your body starts diverting resources away from your muscles to cool your core temperature down. This degrades your performance & endurance and impairs your focus and reaction time. You end up getting tired faster because you deplete your glycogen stores and accumulate lactic acid faster.

Ghost Towns

Called the Mother Road, Route 66 was once the main thoroughfare that connected these smaller “Main Streets” to the rest of the country. However, after Route 66 was decommissioned and the interstate system realigned the roads away from many of the towns, some have faded away.

The practical reality of that is, unlike the first half of Route 66 from Chicago to Amarillo, which was mostly densely populated, there are stretches of this ride that are without services for 40-60 miles through mountainous arid land. One of the toughest days will be crossing the Mojave into California from Arizona, we’ll have to ride 110 miles to get to the nearest hotel!

Weather Variability

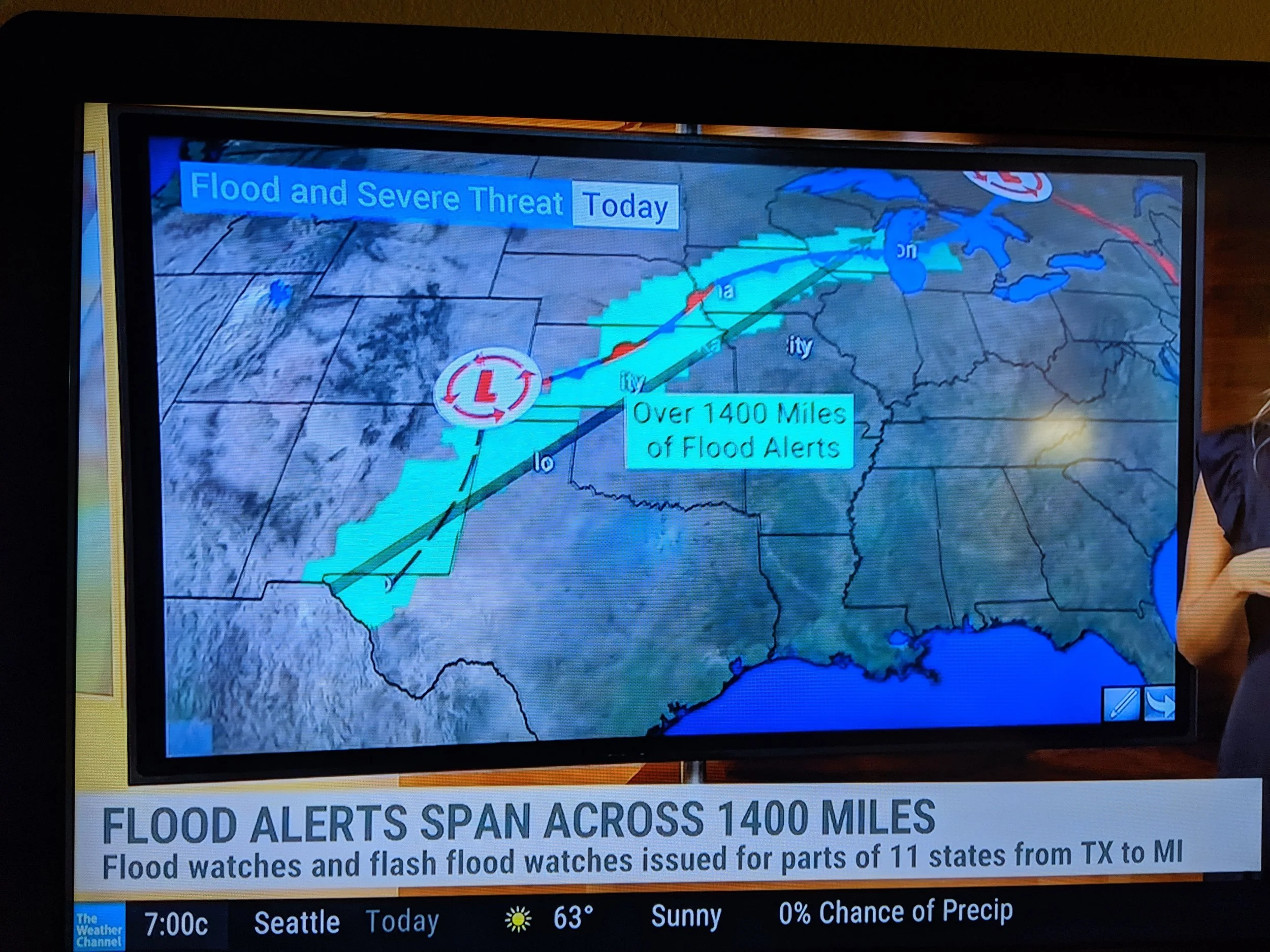

Since it’s generally hot everywhere in the south during the summer, it’s best to wait until any other season to ride. However, during the winter months, the Jet Stream, the westerly winds that blow in from the Pacific Ocean and across the US, are the strongest. In fact, check out the estimated times on your flights from East to West when crossing the US in the winter, they can increase by 15-60 minutes!

Since you can’t ride in the summer or winter, that leaves spring or fall, and since fall is soon, that’s what I’ll go with. The temperatures in Amarillo and Albuquerque are historically around (80/50°F high/low). Gallup (70/40F), Flagstaff (70/35F) with some snow possible, and in the Mojave (90/60F) with temperatures up to 100 still possible. There are also flash floods possible in the desert areas. During the first part, there were flash floods in the three days leading up to my arrival in Amarillo. Generally, I think it will be too hot with the possibility of sudden flash floods.

What Can I do to Prepare?

At heart, I’m a prepper. I love to talk about the apocalypse and what preparations I’d make. My favorite character in The Last of Us is, obviously, Bill. So, I don’t want to be all doom and gloom, only cognizant of the uphill battles. (Sorry, Dad joke.) None of these issues are insurmountable and all can be prepared for to a certain degree. There are a couple of things which I probably won’t get to, but I hope my general training and fitness will help me rise to the challenge. So here is how I’ll prepare or train:

Elevation: While I could do a couple of training rides at elevation in the Sierra Nevadas near Lake Tahoe, that ship has sailed. This is one of those issues, and it’s a pretty big one, where I’m rolling the dice and hoping for the best.

Mountains: I live in the San Francisco Bay Area. As such, there are hills galore on which to train. My favorite 10-mile route has a 6-mile, 1,500ft ascent where the grade is at times 9-10%. My thought is, if I practice this a few times a week and layer in some longer rides, I’ll at least get my body used to ascending those mountains.

Deserts & Hot Weather: Again, living in the Bay Area, there isn’t a lot of weather variation, which is a huge upside for life but a downside for preparation. All year round, the weather here is around 60-70°F. There isn’t a lot of heat training in my immediate vicinity. In fact, just the other day, I rode into a neighboring town, just a tunnel away, and it was 90°F! During that 43-mile ride, my chain broke, I ran out of water, and we had to hop some fences to get around a construction zone. If we just double the mileage, it could be representative of the obstacles to come.

In terms of the sun, I’ll be wearing a lightweight sun-shirt. Hopefully, this will keep me cool and keep the sun exposure down. If it rains, I’ll have a raincoat. I don’t anticipate it being too cold while I’m riding, so I’m not going to worry about that.

Ghost Towns: All along the second half of Route 66, there are a lot of areas where there are no services or hotels, sometimes for 40-50 miles. I’ve been practicing carrying more water and weight on my bike and really trying to dial in my nutrition needs.

On top of all this preparation, a very unexpected change to my plans will help. My retired father has decided to accompany and support me for one of the more isolated portions of the route. And my bestie has decided to accompany me for another, which has raised my morale, alleviated some stress, and will provide just that little bit more time to help me acclimate.

To tube or to tubeless?

What are the considerations to go tubeless?

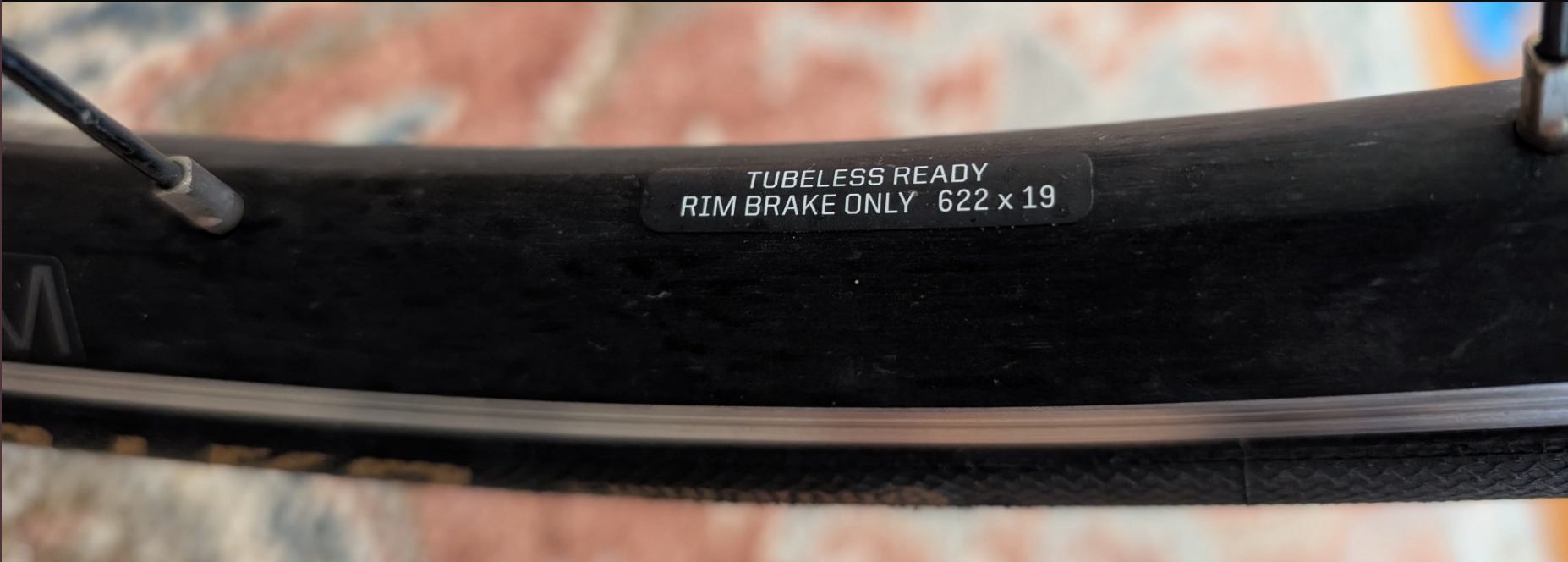

When I got my bike in 2019 I noticed this tiny little sticker on the rim of my front wheel. It says “Tubeless Ready.” Since I had purchased the bike sight unseen and started the first half of my Route 66 ride when I picked it up in Chicago, and as someone who is only moderately comfortable with my bike and all the surrounding gear, see post about new cycling shorts, I completely disregarded it. Note, I only got two flats the entire time on the first half.

Fast forward to 2025. Intrigued by the sticker and a suggestion from a friend, I’m looking into changing things up this time around. Since riding 1,200 miles across mountains and desert on a somewhat deserted road will be demanding, given the long days, mixed road quality, and remote stretches; reliability and dependability matter as much as performance. My considerations are:

Road conditions: Route 66 has notoriously rough asphalt, chipseal, and debris (wires, glass, goatheads in the desert)

Remoteness: Some stretches are far from shops—repairs need to be self-sufficient.

Distance & Duration: I’ll be on the bike for weeks; minimizing time spent fixing flats is valuable.

Load: I’ll have at least 15-20lbs worth or gear and water

The argument for tubeless is that there will be fewer flats, no pinch flats (when hitting potholes or cracks with weights), and being able to ride with lower tire pressure. The last time around both my flats were egregious punctures so I’m less worried about pinch flats. The downsides are that I’d need to bring extra sealant and a plug kit. If there is a big puncture, it would create a big messy sealant leak AND I’d need an inner tube and pump any way. Finally, I’d have to learn, test, implement this new system before I leave. Apparently installing a tubeless tire requires some professional consultation (ahem, youtube). And in hot weather the sealant dries out faster requiring inspection and additional sealant every one or two months as opposed to 3-6months.

Since I am going to replace my old tires, Continental Gatorskins, any way, my plan is to get the Schwalbe Marathon Almotion TLE which was specifically designed for touring with tubeless or the Marathon Efficiency TLE in a 28mm. I’ll test these on a few local rides and if I like it, I’ll stick with the tubeless. During my ride, I’ll take a hybrid approach and carry sealant, inner tubes, and a pump. This doesn’t help me minimize the necessary gear but it might help me avoid the inconvenience of changing a flat tire in the sweltering heat of the desert.

On breathing, meditation, and zen sports

Or how I will stop mocking things found on Tik Tok.

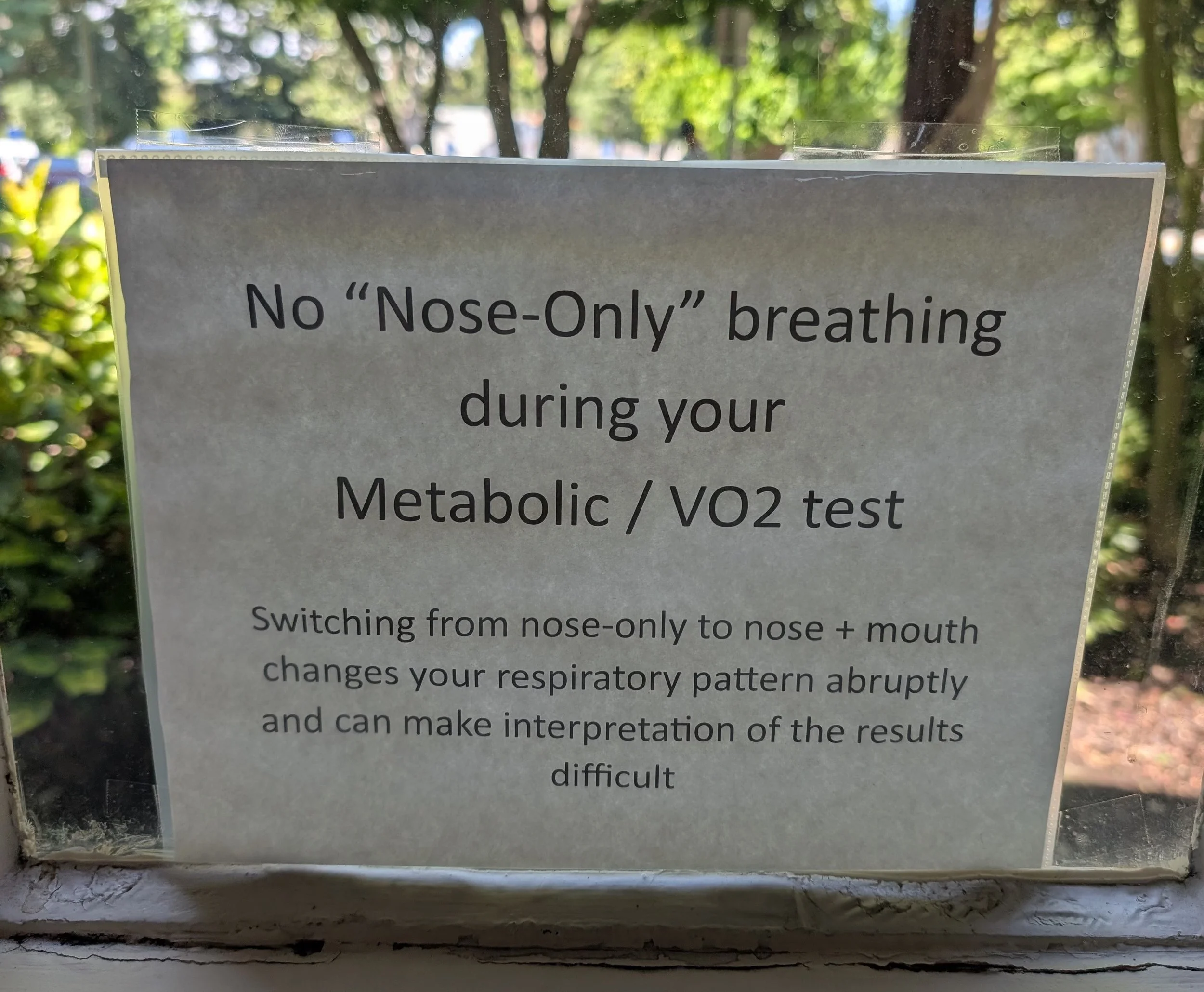

While I was taking my lactate threshold exam at UC Davis, this sign was taped to the window right in front of my bike. My test administrator shared with me that nose only breathing has been making the social media rounds. Naturally, I mocked it because it sounds ridiculous. Why only use half of the resources you’ve been given? When I start to work out hard, I always breathe in through my nose and out of my mouth.

I didn’t give any of this a second thought until I was almost at the end of the exam and I had started to get into my standard “working hard” breathing rhythm which is consists of two short nose inhales and one long and very loud mouth exhale. As a long time casual runner, I naturally fall into this breathing pattern because it lowers my heart rate which enables me to run longer without fatiguing as easily. The test administrator remarked on my heart rate staying pretty even, despite my comical inability to push the pedals any more.

A week passes and I stumble across the book Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art, by James Nestor from 2020. Side note, I got pregnant during the pandemic, this guy writes a seminal work and NYTimes bestseller. Some people know how to manage their time well. The key themes are that modernity has altered the human skull narrowing airways and shrinking the face so that mouth breathing is more widespread. Chronic mouth breathing leads to a whole host of maladies. However, if we all just learn to breathe ‘correctly’ through our nose, then we might not have as many problems - like sleep apnea, diabetes, schizophrenia, or even scoliosis. It sounds like I’m mocking again, and maybe I am, a little, but he has a point.

I grew up ensconced in Buddhism, the way some people go to vacation bible school so they can learn about God year round. Meanwhile, I was learning about meditation. Can you imagine an ADD child trying to stay calm and still for 30 minutes? Everyone else was lucky if all I did was fall asleep. By the way, one teaching that stuck with me was that monks are forbidden to eat 5 foods, in addition to meat. Those are garlic, onions, leeks, chives, and asafoetida. People have speculated why but a child can tell you eating those can lead to distracting yourself and others who are practicing breathwork.

Another side bar: Check out this guy’s substack on Buddhist chants and breathwork.

In Breath, Nestor explores the Tibetan Tummo technique, a breathing and visualization practice used by monks to generate heat and potentially withstand extreme cold. Nestor highlights how this ancient practice, which involves stimulating the sympathetic nervous system, can significantly raise body temperature. In her effort to convince me to meditate more, my mother used to tell me the same story which I thought was a work of maternal fiction bourn out of frustration, see ADD part.

However, no amount of sitting still ever worked for me. It wasn’t until in college, when I started running, that I was able to clear my mind and enter the blissful zen state known as Runner’s High. From there, breathwork like nasal breathing, deep breathing, or fortifying your diaphram — all are easier because your body is singularly focused on getting more oxygen to your muscles.

I subsequently found swimming to be the best sport for breathwork due to the nature of timing your breaths and being forced to hold it for longer intervals or trickle your exhalation. Nestor points out that breathing isn’t about getting more oxygen but about managing CO2. When balanced, CO₂ becomes a powerful ally, helping your body use oxygen efficiently, reducing stress, and optimizing overall health. Perhaps there is something chemical happening too as a result of possibly having more CO2 in your body.

My final thought which I’ve been dancing around is to read the Breath book. Nestor is a good writer. He masterfully weaves the language of science, history and personal experience with evocative and relatable ideas. Like the following which really appeals to someone who smells things as a day job.

“Smell is life’s oldest sense… breathing is so much more than getting air into our bodies. Its the most intimate connection to our surroundings. Everything you or I or any other breathing thing has inhaled is hand me down space dust thats been around for 13.8bn years.”

What are your zen sports or the ones which make you feel the most calm or euphoric? Any breathing experiences you’d like to share? What did you think of Nestor’s book?

Gear List

What's necessary and what's a luxury?

Gear from 2019 Chicago - Amarillo ride. Not pictured: three bike bags & my phone.

When you’re carrying everything, you learn to only bring what is absolutely necessary. I learned this the hard way while hiking to Everest Base Camp in Nepal a few years ago. I’ve always lived at sea level so the trek to around 17,000ft became laborious due to the elevation. My pack weighed 28lbs and that didn’t even include a tent or cooking gear. In my defense, it was my first time backpacking on my own. (Why would you choose Everest Base Camp as your first backpacking experience? Go big or go home as my Texan brethren would say). When I embarked on the Annapurna Circuit a few weeks later, my pack was a spry 12lbs.

Pictured above is what I brought on the ride in 2019. Pictured below is what it looks like when I first start out coming fresh off the plane.

Here is the full list from 2019*:

On the Bike: seat post bag, frame bag, handle bar bag, water bottles (2), front light, tail light, phone holder

Tools: phone + charger, headphones, pump, multi-tool, tire levers, inner tubes (2)

Riding: sunglasses, helmet, cycling shoes, gloves, Garmin watch + charger, underwear, sports bra, Pearl Izumi Sugar 5in shorts, jersey, socks, rain jacket, buff

Resting: glasses, ballet flats, underwear, bralette, yoga pants, long sleeve shirt, puffy, neck gaiter

First Aid: Ibuprofen, bandaids, dermabond

Toiletries: comb, conditioner, face lotion, tooth brush / paste, sunscreen, lip balm, nail clipper

Other: wooden spoon, small laundry detergent, battery pack, electrolyte tablets, razor

Changes for 2025:

There aren’t many changes, because you don’t need much when all you’re doing is biking from dawn until dusk. Also, why did I bring a wooden spoon? Changes? For starters, I’ll most likely cut the entire “other” category. I’m toying with the idea of replacing my glasses/sunglasses/headphones with a pair of Ray Ban Meta smart glasses, but still debating since they are known to slide down your nose — alot. Additions: Selfie stick, shotgun mic, long sleeve shirt, riding hat, detergent bar. I’m also going to try out a set of women’s specific Terry Cycling high rise shorts. However, at $130, they better be like sitting on a cloud compared to my $40 Pearl Izumis.

*These are not sponsored links and I do not get any kickbacks for them. They are here so you can get a sense of what I used and a convenient link if you want to buy them.

A Centennial's Significance?

Will our AI overlords celebrate the centennial of Dial-Up technology in 2058? Is there something sacred about physical places or arterial paths?

Next year marks the centennial of the most famous road in the United States. Established on November 11, 1926, Route 66 was one of the original highways in the U.S. Numbered Highway System. Stretching 2,448 miles from Chicago, Illinois, it passes through Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona before reaching its western terminus in Santa Monica, California, where the continent meets the Pacific Ocean.

Often called the “Main Street of America” or the “Mother Road,” Route 66 connected the densely populated urban centers of the Midwest—closely tied to the East Coast—to the wide-open frontier of the American West.

Yet as the 100-year anniversary approaches, one has to wonder: what exactly are we commemorating? Route 66 was officially decommissioned in 1985. Many once-vibrant communities along its path—Texola, Texas; Glenrio, New Mexico; Oatman, Arizona; Amboy, California—have faded into near–ghost towns. Isn’t Route 66 simply an outdated road, long since replaced by faster, wider, more efficient interstates?

Will our future AI overlords celebrate the centennial of dial-up internet in 2058? Is there something inherently sacred about physical gathering places or the arterial routes that once bound a nation together? Or are we really trying to revive the idea that we can be united by a shared dream—something larger than asphalt and infrastructure, something that transcends its physical form?

What is it about this highway that has so beguiled a nation? Roads crisscross the country, yet no equivalent within today’s Interstate system seems to capture the same spirit. Route 66 endures in the American imagination because it embodies powerful cultural myths and lived realities that resonate deeply with the national identity.

More than pavement and signage, the highway came to represent the quintessential American promise of mobility and reinvention. It served as a primary artery for westward migration—most famously during the Dust Bowl, when families fled economic devastation in search of opportunity in California. That movement echoed the nation’s foundational narrative: go west, leave the past behind, begin again. When the world looked to America as the “land of opportunity,” Americans themselves looked westward. Even Don Draper eventually made his way to California.

Route 66 also symbolized freedom and adventure in a distinctly American way. Unlike the efficient but impersonal interstate highways that replaced it, the old road wandered through small towns, past neon-lit motels, roadside attractions, diners, and motor courts. Its planners intended it to link the main streets of rural and urban communities—many of which had never before been connected to a major national thoroughfare. It offered travel on a human scale, where the journey mattered as much as the destination.

That sensibility aligned with enduring American ideals of individualism and self-determination—ideas that, unlike the highway itself, have proven remarkably long-lived.

Finishing what I started

In 2019, I rode my bike from Chicago, IL, to Amarillo, TX, along the historic Route 66 highway. Now, six years later, I'll complete the journey and ride on to Santa Monica Pier in LA.

In 2019, I rode my bike from Chicago, IL, to Amarillo, TX, along the historic Route 66 highway. Now, six years later, I'll complete the journey and ride on to Santa Monica Pier in LA.

Street marking along Route 66

One of my favorite quotes is by the Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen. He intentionally wedged his ship, the Fram, into the polar ice floes, trusting that the current would carry him toward the North Pole. His innovations in equipment, clothing, and travel methods would go on to influence generations of polar explorers. He says:

"it is within us all... our mysterious longing to accomplish something, to fill life with something more than the daily journey from home to office. It is our ever present longing to surmount difficulties and dangers, to see that which is hidden... it is the call of the unknown, the longing for the land beyond, the divine power deeply rooted within the soul of man… the force of human thought which spreads its wings and flies where freedom knows no bounds."Cycling from one city to another in a first-world country along a defunct highway—where countless others have ridden before—is hardly a dazzling act of exploration. And yet, every few years, I’m overtaken by a powerful desire to shake the captivity of my ordinary world. To shed complacency and become one with the elements. To push my body and mind until they move in sync. To see beyond the boundaries of routine. To remember that anything is possible.

Six years ago, I planned the first half of the trip in eight days, bought a bike, and rode 1,200 miles in 17 days. My preparation amounted to answering two questions: “Will there be a bike available in Chicago when I land?” and “Can I keep my legs moving for eight to nine hours a day?”

This time, I have the luxury of a four- to five-month lead-up. I even own a bike.

I’m going to use this space to document the planning, the training, my evolving fitness and nutrition—and, of course, the ride itself. Join me as I prepare for the journey and discover what it does to my body along the way.

Me pretending to be at the end, History Museum on the Square in Springfield, MO. A must visit!