A Centennial's Significance?

Will our AI overlords celebrate the centennial of Dial-Up technology in 2058? Is there something sacred about physical places or arterial paths?

Next year marks the centennial of the most famous road in the United States. Established on November 11, 1926, Route 66 was one of the original highways in the U.S. Numbered Highway System. Stretching 2,448 miles from Chicago, Illinois, it passes through Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona before reaching its western terminus in Santa Monica, California, where the continent meets the Pacific Ocean.

Often called the “Main Street of America” or the “Mother Road,” Route 66 connected the densely populated urban centers of the Midwest—closely tied to the East Coast—to the wide-open frontier of the American West.

Yet as the 100-year anniversary approaches, one has to wonder: what exactly are we commemorating? Route 66 was officially decommissioned in 1985. Many once-vibrant communities along its path—Texola, Texas; Glenrio, New Mexico; Oatman, Arizona; Amboy, California—have faded into near–ghost towns. Isn’t Route 66 simply an outdated road, long since replaced by faster, wider, more efficient interstates?

Will our future AI overlords celebrate the centennial of dial-up internet in 2058? Is there something inherently sacred about physical gathering places or the arterial routes that once bound a nation together? Or are we really trying to revive the idea that we can be united by a shared dream—something larger than asphalt and infrastructure, something that transcends its physical form?

What is it about this highway that has so beguiled a nation? Roads crisscross the country, yet no equivalent within today’s Interstate system seems to capture the same spirit. Route 66 endures in the American imagination because it embodies powerful cultural myths and lived realities that resonate deeply with the national identity.

More than pavement and signage, the highway came to represent the quintessential American promise of mobility and reinvention. It served as a primary artery for westward migration—most famously during the Dust Bowl, when families fled economic devastation in search of opportunity in California. That movement echoed the nation’s foundational narrative: go west, leave the past behind, begin again. When the world looked to America as the “land of opportunity,” Americans themselves looked westward. Even Don Draper eventually made his way to California.

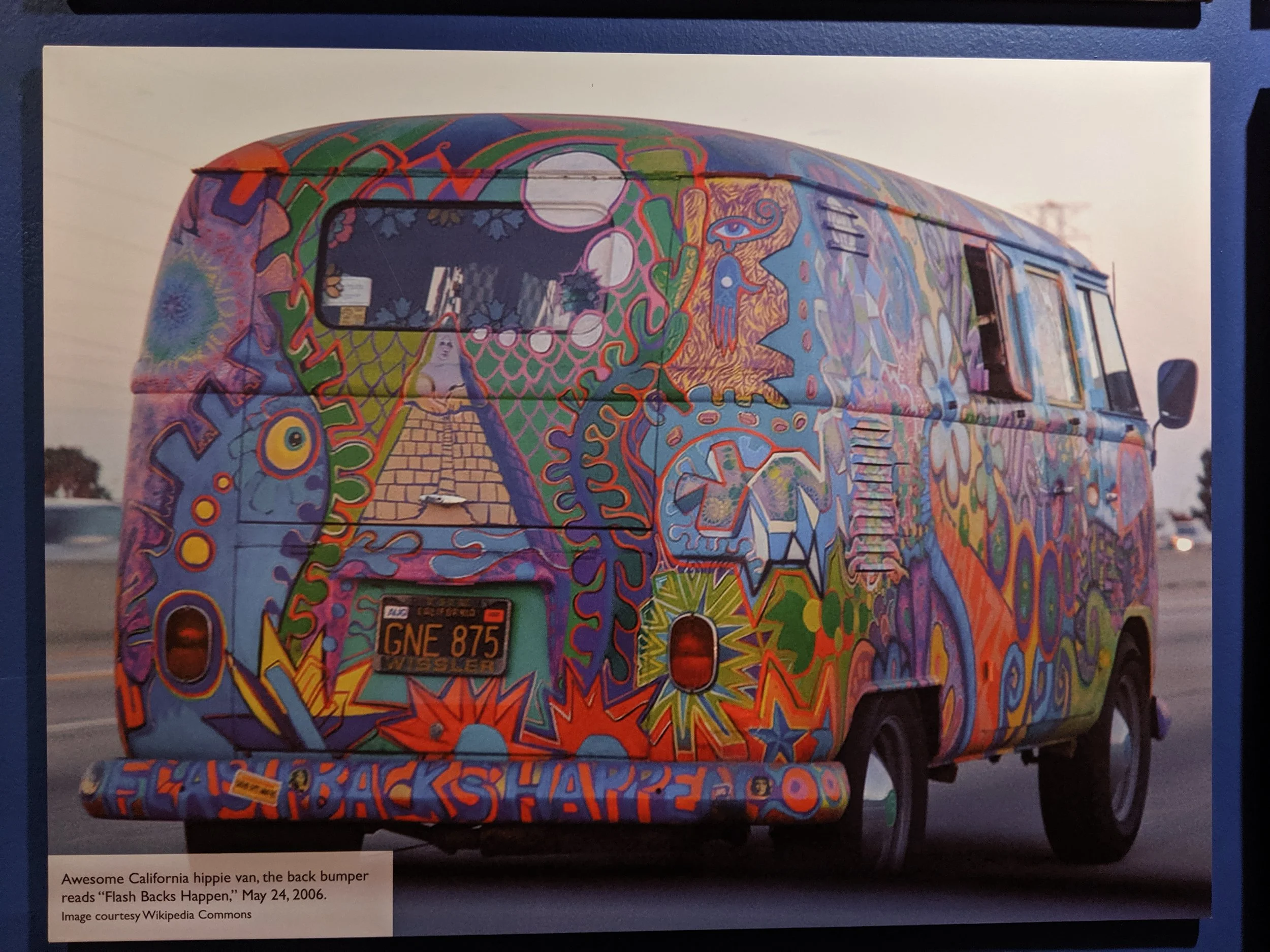

Route 66 also symbolized freedom and adventure in a distinctly American way. Unlike the efficient but impersonal interstate highways that replaced it, the old road wandered through small towns, past neon-lit motels, roadside attractions, diners, and motor courts. Its planners intended it to link the main streets of rural and urban communities—many of which had never before been connected to a major national thoroughfare. It offered travel on a human scale, where the journey mattered as much as the destination.

That sensibility aligned with enduring American ideals of individualism and self-determination—ideas that, unlike the highway itself, have proven remarkably long-lived.